Celebrating the life and reactive output of one of the most influential and original filmmakers in the history of cinema, words by Jacques Marie Mage.

By the time director Stanley Kubrick began principal photography on his final film, Eyes Wide Shut, in 1996, he had been living in England for over 35 years. As the United States wandered blindly into the 1960s, still beaming from the pristine kitchen-countertop sheen that characterized much of suburbia in midcentury America, the Bronx-born filmmaker felt stymied by the formulaic conventions that Hollywood demanded. Fleeing for both a change of scenery and the freedom to make his adaptation of Vladimir Nabokov’s controversial novel Lolita , Kubrick was unencumbered by the moral panics American journalists stoked for sport, eventually settling into a sprawling manor in the English countryside, about a 30-minute drive from London, where he lived until his death in 1999, at age 70.

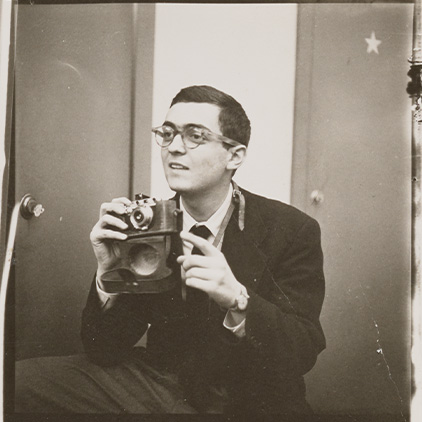

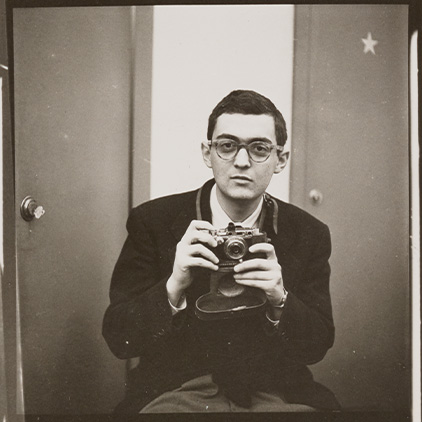

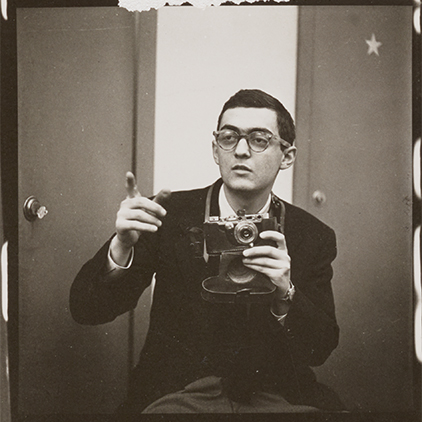

But it was in New York City, as a teenage photographer for Look magazine, that Kubrick began to hone a visual style, a way of seeing, that became the template for a dozen cinematic masterpieces still unrivaled by legions of contemporary acolytes, from Paul Thomas Anderson to Denis Villeneuve. Starting at age 14, armed with a Graflex camera his father gave him for his birthday the previous year, Kubrick embarked on a five-year journey of education and self-discovery, in lieu of college, after barely escaping high school. Between 1945 and 1950, he published images alongside nearly 135 pieces in Look, a bi-weekly to rival the ever-popular Life magazine.

Look’s photo editor, Helen O’Brien, had purchased many of Kubrick’s early images, publishing his first-ever “professional” photograph of a newspaper vendor surrounded by the death notices of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Seeing in Kubrick something that might have eluded photo editors less intuitive or astute than O’Brien, she offered the soon-to-be graduate of William Howard Taft High School a salary of 50 dollars per week as an apprentice, unaware that her admiration for a teen photographer, hired on the cheap, would inadvertently launch the career one of the 20th century’s greatest auteurs.

Where Life rushed to aim its lens to capture the topline stories of the day, Look turned toward regular people at regular places—poolhalls, zoos, boxing rings, racetracks, a dentist’s waiting room—and the everyday intersections of personalities and moods that characterized actual life in the streets of the city Kubrick first called home. This allowed the young visual stylist the opportunity to find a pace and a rhythm not tied to current events, freeing him to construct narratives, to tell stories, and to begin to formulate his infamous fealty to fastidiousness, detail, control, and a lifelong pursuit of the perfect shot—perfection as defined by Kubrick’s eye alone.

Another unforeseen contribution to Look that O’Brien may or may not have known at the time of Kubrick’s hiring, was how his youth and eagerness to learn would not just earn him illustrious mentors at the magazine—like more experienced, older photojournalists Arthur Rothstein and John Vachon—but invigorate the longtime staffers as well. Photographers at Look even created the Bringing Up Stanley Club, a communal effort to not only inform his image-making practice, but his entrée into adulthood as well, including career and sartorial advice. Kubrick advanced from apprentice to staff photographer in less than a year.

Under the ongoing tutelage of Rothstein, Kubrick first began photographing boxers in 1947, including a fight between lightweights Bobby Ruffin and Wille Beltram. Although they were not published, the brutality of the sport and its impressive athletes became a subject that captured Kubrick’s imagination. By 1949, Kubrick had accompanied Rothstein and Vachon to fight nights at Madison Square Garden. In January of that same year, Kubrick published his photo essay, “Prizefighter,” chronicling the daily life, routines, and performance in the ring of middleweight Walter Cartier. It was his most-significant contribution to date at Look, featuring the best of his 1,200 photographs over a seven-page spread. If hindsight affords us the luxury of anointing a “turning point” in a long, celebrated career of image-making, it was these early photographs that would inspire Kubrick’s first attempt at filmmaking: The Day of the Fight, 1951, a 16-minute self-produced documentary, the subject: Cartier.

Kubrick’s learned ability to reveal the private and public life of well-known figures in a narrative style, over the course of multiple pages, earned him the trust of Look’s assigning editors to send him beyond the boxing ring and into the homes of celebrated New York celebrities, socialites, and artists. His images of former New Yorker cartoonist Peter Arno include the subject contemplating nude models in his studio, intimate images of him with tousled hair rummaging through the day’s paper in bed, and later in the evening, adorned in a tux, whispering into the ear of an actress at a bar. By late 1949 and early 1950, Kubrick had contributed photographic portraiture and essays with subjects as diverse as conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein and debutante Betsy von Furstenberg, the latter assignment earning Kubrick one of his three covers for Look.

From his early on-the-ground shots of daily life to his composed and refined essays for Look, Kubrick worked alongside a burgeoning post-war, New York street photography culture that had no lack of talent. The period produced timeless images from young artists who could find enough spontaneous encounters and unusual characters engaged in everyday activities on a single street corner in one afternoon to churn through a dozen rolls of film. Had Kubrick’s love of literature, storytelling, and narrative not led him into the ‘50s (and his early 20s) with his heart set on cinema, his reputation as a photographer might have rivaled those of his contemporaries who often worked the same beat—William Klein, Garry Winogrand, Elliott Erwitt, and Lee Friedlander, to name but a few.

Now, it’s Kubrick’s own life’s narrative that colors his black-and-white images for Look. It’s impossible not to impose one’s knowledge of his filmmaking to force some linear progression from his earliest photographs in 1945 to those he made toward the end of his employ at the publication. It’s impossible because the evidence is clear.

In an early series, published as “Dentist’s Office: Americans Are Dutiful but Nervous Dental Patients” in the October 1946 issue of Look, Kubrick created something akin to a two-page film reel of 18 individual photographs, documenting the anxieties of New Yorkers awaiting a dreaded checkup. By 1949, entrusted with capturing the homelife of newly anointed Hollywood star Montgomery Clift, you will see the work of a confident Kubrick in rhythm with a willing performer.

His time spent at Look photographing boxers clearly inspired his carefully composed scenes of the same sport in his 1955 film Killer’s Kiss . His series of photos capturing the arrival of Dwight D. Eisenhower as president of Columbia University, sees Kubrick wandering away from the obvious documentation of pomp and prestige, more intrigued by the faculty engaged in scientific experiments. One memorable image shows a professor wearing glasses with darkened lenses, holding aloft an illuminated tube that Look merely captioned as “some kind of research.” Anyone who has seen Dr. Strangelove might feel a similar unease at this still image that evokes some of the professorial mania, the hubris of a scientist unafraid of the radiating tube whose particular use can only be guessed at, not unlike a part made to fit a doomsday machine.

In the essay, “Learning to Look,” written to accompany an exhibition of Stanley Kubrick’s work for the magazine, critic Luc Sante writes of the young photographer’s “fanatical attention to detail” and his ability to tame the chaotic daily life of the city “as a vast studio in which no nuance goes overlooked, and nothing is left to mere chance.”

Kubrick’s first published photograph in the June 1945 edition of Look, of a somber newsstand attendant surrounded by pronouncements of FDR’s death, is connected to the last work he completed. In Eyes Wide Shut, Tom Cruise pauses at a kiosk to purchase a copy of the New York Post with the headline “Lucky to Be Alive,” before wandering down a replica of a rain-slick Manhattan neighborhood street that the filmmaker had commissioned to be built inside England’s Pinewood Studios. Stanley Kubrick may have left New York and behind, but neither left him, right up to the final frames of a body of work that will forever remain bookended by the city he loved, the city that raised him.